It’s no good writing about the upper-classes if you hope to be taken seriously… Station masters, my dear, station masters.

From Christmas Pudding (1932).

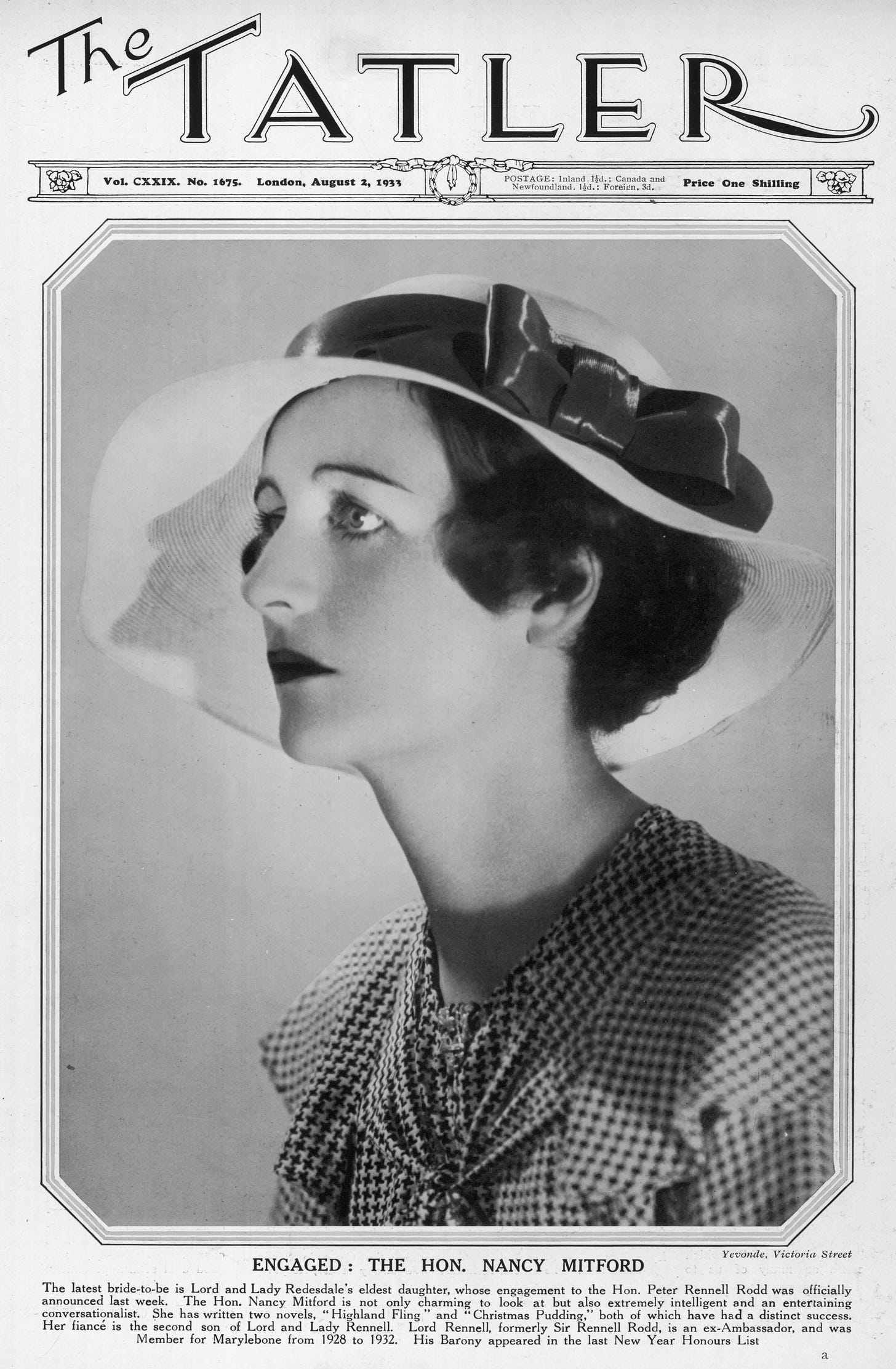

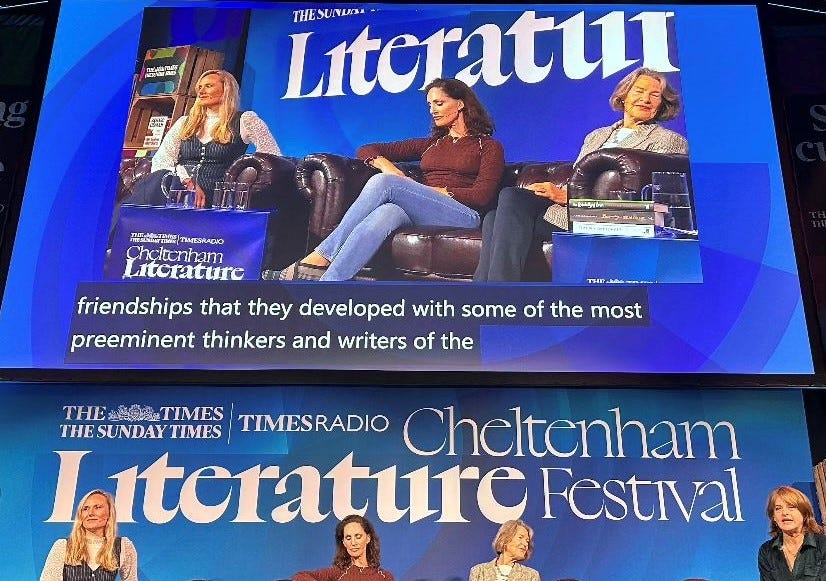

Lately I’ve been in the wonderful world of Nancy Mitford. A couple of weeks ago I was talking about her at the Cheltenham lit fest (below, with the very lovely Kate Kirkpatrick (left) and Ariane Bankes)…

… and now I’m preparing for a little gig discussing one of her novels on R4. An early book: Christmas Pudding.

I hadn’t read it for years and I am amazed by how good it is. Inconsequential, one might say, in that it is simply the tale of a group of privileged people who spend the holiday season in Gloucestershire and talk a lot, mostly about love: Manhattan goes to Moreton-in-Marsh. It is a satire, of the mildest kind, upon Nancy’s own social milieu: Vile Bodies without the vileness.

The plot is near-non-existent - who will fall in/out of love with whom, is about the size of it - and the characters are almost like in-jokes for Nancy’s own young set: for instance the lead male, Paul Fotheringay, bears a strong resemblance to John Betjeman (famously in love with Pamela Mitford, although he described Nancy as ‘the warmest of them all’). Meanwhile the wretchedly precocious Bobby Bobbin (that name one of the very few jokes that doesn’t land) is a representation of Hamish St Clair Erskine, the aristocratic homosexual with whom Nancy had decided to be in love, despite the fact that he had slept with her brother, and on whose account she had made an insincere attempt at suicide in early 1931.

To be fair to Hamish, he is partly to be thanked for the fact that Nancy began writing at all. She wanted money to be able to go about with him, occasionally to lend him – he was four years younger than she, a student at Oxford with wasteful habits – or, as she wrote in 1930, to save towards her marriage: ‘Evelyn [Waugh] says don’t save it, dress better & catch a better man. Evelyn is always so full of sound common sense.’

And Evelyn, as usual, was right.

This rather strange and naive passion only ended in June 1933, when Hamish - doing the right thing in the wrong way - announced that he had become engaged to another woman (unsurprisingly the marriage never took place). Very much on our old friend the rebound, Nancy became instantly engaged to Peter Rodd, the infamous Prod, good on paper (Eton, Balliol, rather handsome, clever as you like) and pretty poor everywhere else (feckless and adulterous). Evelyn again:

I hope that Mr Erskine will now disappear from your novels. But listen, I won’t have you writing books about Rodd because that would be too much for me to bear.

When Nancy wrote Christmas Pudding, however, ‘Rodd’ and the grim realities of misalliance were in the future. She was still, at the time, entangled with the thorny little Hamish; still - apparently - thinking that dreams of wedded bliss might by some peculiar means come true. Or did she, in her heart? Because the observations in this youthful novel land like so many arrows on a bull’s-eye, and in particular when targeting the subject of marriage - as when the best character in the book, Amabelle Fortescue, an ex-prostitute turned respectable middle-aged femme fatale, says:

If I had a girl I should say to her, ‘Marry for love if you can, it won’t last, but it is a very interesting experience and makes a good beginning to life. Later on, when you marry for money, for heaven’s sake let it be big money. There are no other possible reasons for marrying at all.

Cynical? Perhaps. But at a time when marriage was everything - the only feasible way forward for most women, rather than the life-choice that we now consider it to be - I would rather call it admirably realistic. ‘I must say’, the magnificent Amabelle tells a silly young couple, hellbent upon engagement, ‘that it would be much easier, more to your mutual advantage and eventual happiness, if you could bring yourselves to part now and lead different lives’.

But that kind of sense is never something that lovers want to hear. And in 1931 Nancy was no exception, even when it was her own self who was telling her.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Laura Thompson’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.