Yesterday was the autumnal equinox, definitively the start of the year’s fall. In consolation I always think of the protagonist in Agatha Christie’s The Hollow, staring out at a red-gold world and saying to herself: ‘I love autumn. It’s so much richer than spring’. But the first weeks of autumn always hold for me a heavy, fateful quality, unrelated to the end of summer.

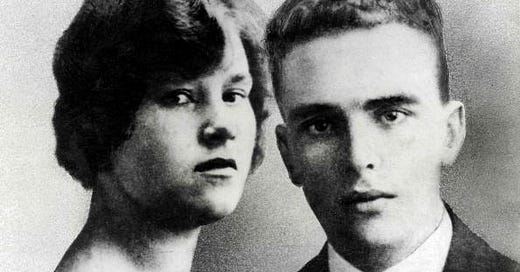

From around this time I start to think - cannot help but think - of events that took place more than a century ago now, in late September 1922: of twenty-year-old Freddy Bywaters sailing slowly back to England on his merchant ship, after a tour that had begun back in June, during which he had received numerous long letters from his lover, Edith Thompson, a married woman some eight years his senior. She had destroyed his replies, but from her own words it is clear that he had been trying to end their relationship, or at least to persuade her to be ‘pals only.’

The fact that he did not do so - did not break off contact entirely - led to three deaths.

I have written before about this story, the one that I first read about as a teenager and that the newspapers of the time - which could not get enough of it - called the ‘Ilford Murder’; a story that culminated at around midnight on 3rd-4th October 1922, when Freddy Bywaters stabbed Percy, fatally, during a prolonged scuffle, in a street near the Thompsons’ marital home. Percy and Edith had been walking back from Ilford station after an evening at the Criterion theatre.

Freddy was soon arrested, charged and tried. He was hanged at Pentonville on 9 January 1923. So too, a couple of miles away at Holloway, was Edith Thompson.

There was no proof that she had anything to do with the killing of her husband, no material evidence of foreknowledge or complicity. In his death cell Freddy insisted that she had not known what he was going to do that night; I am not sure that he himself knew either, but a verdict of manslaughter would have exonerated Edith, which was not at all what anybody (bar a few free-thinking exceptions) wanted to happen. ‘Thank you for defending the honour of my sex’, a woman wrote to the Home Secretary, when he refused to commute the death sentence on Edith Thompson. ‘Even those who objected in principle to her execution can hardly regret her absence from the sphere’, wrote The Times newspaper.

What had condemned her, in the courts of the Old Bailey and public opinion, were her own words: the letters that she had written to her lover, which were used by the legal system to ‘prove’ that she had conspired with Freddy and incited the crime. The letters do indeed contain - within their many thousands of words - repeated references to administering poison or ground glass to Percy Thompson; although the autopsy revealed that his body contained no such substance.

The letters induced a secondary condemnation, moreover, against Edith herself: an adulterous woman; a childless working woman, without much education, but with ambition and aspiration and extraordinary powers of attraction, who expressed emotion in a way best described as Lawrentian; an older woman (getting to the heart of it here), leading a fine young man astray. The moral prejudice thus induced became impossibly entangled with the murder accusation. A woman capable of writing such things, went the ‘logic’, was capable of anything.

I edited these remarkable letters for publication by Unbound at the time of the centenary. The book Au Revoir Now Darlint: The Collected Letters of Edith Thompson is out in the US in December. I loathe the concept of ‘relevance’ - a story is either interesting or it isn’t - but there is no question that, in a society when words can no longer hang you, but can - if insufficient care is taken with them - render you outcast, obsolete, imprisoned, what happened to Edith is indeed appallingly relevant.

As I wrote in the book’s introduction:

A century before the advent of cancel culture, this woman was cancelled – obliterated – for word crimes, thought crimes, the crime of being herself.

In 1922 today’s date, the 23rd, fell on a Saturday. Freddy’s ship, the Morea, docked that day at Tilbury and Edith had sent him this telegram: ‘Can you meet Peidi Broadway 4 pm’. 'The Broadway’ was in London’s East Ham, near where she and Freddy had grown up. ‘Peidi’ was the intimate nickname that they used.

Having worked a half-day - she was a manager at a millinery warehouse in the City; a responsible job, which today would be called a career, for which she slightly out-earned Percy - she returned to their joint-owned home at 41 Kensington Gardens and cooked lunch for her husband and father. Then she went out at about 3.00, while the men were working in the garden, giving who knows what explanation, and did not return until after 8.00. According to the Thompsons’ sitting tenant, Mrs Lester, Percy ‘had words with her over being out so long’.

Yet Freddy had not turned up. His ship had docked late, but even so he may have simply decided not to go. What she felt can only be imagined. What she did throughout those long hours, which stretched beyond the setting of the autumn sun, is unknown. Her lover’s written assertions that he would not see her again, at least not as a lover – which she had probably, despite all the anguished pleading, not really believed – had suddenly acquired reality.

It was not Edith’s style to play hard to get, her allure was of a different kind: insistent, insinuating. She was still not prepared to let it go, to say to herself this rude little bastard has stood me up, right, sod him. Had she done so she might have lived to be an old woman. She had no real intention of leaving her marriage; its durable, dissatisfying yet comfortable quality is exemplified in the fact that on the night of 3 October the Thompsons had been at the theatre together with her aunt and uncle (‘They appeared a most affectionate couple’, the uncle said afterwards). Yet this young man - and, most importantly, the words that she wrote to him - had become identified in her mind with the ‘otherness’, the ‘more’, that her boundless imagination craved, and it seemed that she was quite incapable of enduring the loss of that outlet. So she tried again. On Monday she sent a telegram to Tilbury: ‘Must catch 5 49 Fenchurch Reply if can manage.’

This referred to the fact that her suspicious husband, all too aware that handsome Freddy Bywaters was back in town, had stipulated the train that she must catch home from Fenchurch Street.

At 4.30 pm Freddy was outside Carlton and Prior, her place of work on Aldersgate Street. And at 5.49 he too was on the train.

Edith had succeeded.

Now what?

This is from my first book about this story, Rex V Edith Thompson.

‘Never trust the teller, trust the tale,’ wrote D. H. Lawrence, and as the story of Thompson and Bywaters reached its last chapters it became clear that it had acquired its own momentum, a logic that existed apart from the volition of its narrator-in-chief, Edith. In cases of murder it is natural to look for motivation – ‘motive’ – and here, in this classic example of a triangular relationship, it seemed simple enough; except that it was nothing of the kind. The perpetrator himself had no real explanation for what he had done. It was what he wanted to do at that moment, and it was the culmination of what had gone before. It was both irrational and inevitable. If his co-defendant could be loosely compared with Madame Bovary then he, at the moment of the murderous confrontation, bore a certain resemblance to Julien Sorel in Stendhal’s Le Rouge et Le Noir, whose attack upon the woman that he loved was similarly defiant of analysis: rather it was as if the story itself had compelled the event.

So the Morea sailed into dock at Tilbury, and the lovers – soon to be lovers once more, as Edith had intended, as had always been going to happen – moved towards their endgame.

What follows now is an edited extract from Au Revoir Now Darlint: the last letter that Edith wrote to Freddy before his return to England, plus a shortened version of my commentary. The letter was sent, almost certainly, on 21 September. Just over ten weeks later it would be Exhibit 28 at her Old Bailey trial.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Laura Thompson’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.