First, I must thank the extraordinarily generous people on here who responded to my post about the ballet memoir. I am now pretty sure that I AM going to write that book, and the encouragement/ support of Substack readers has played no small part in that. What a truly splendid arena this is.

Meanwhile, and back with a subject that I have already written about… I’m extremely delighted that Au Revoir Now Darlint: The Letters of Edith Thompson, published by the wonderful Unbound, will appear in the US this December. I have also just sent an episode 1 script on Edith to my agent (as we know that means almost nothing, in terms of whether it will ever transition to screen, although simply to have written it means a lot to me).

So the story of Edith Thompson, and the 1922 murder case in which she played her desperate leading role, is very much on my mind. To be honest it is always in my mind, and has been since I was a teenager; when I read P.D. James’s The Murder Room I recognized this thought, from her detective Adam Dalgleish:

Ever since, as an eleven-year-old, he had read of that distraught and drugged woman being half-dragged to her execution, the case had lain at the back of memory, heavy as a coiled snake.

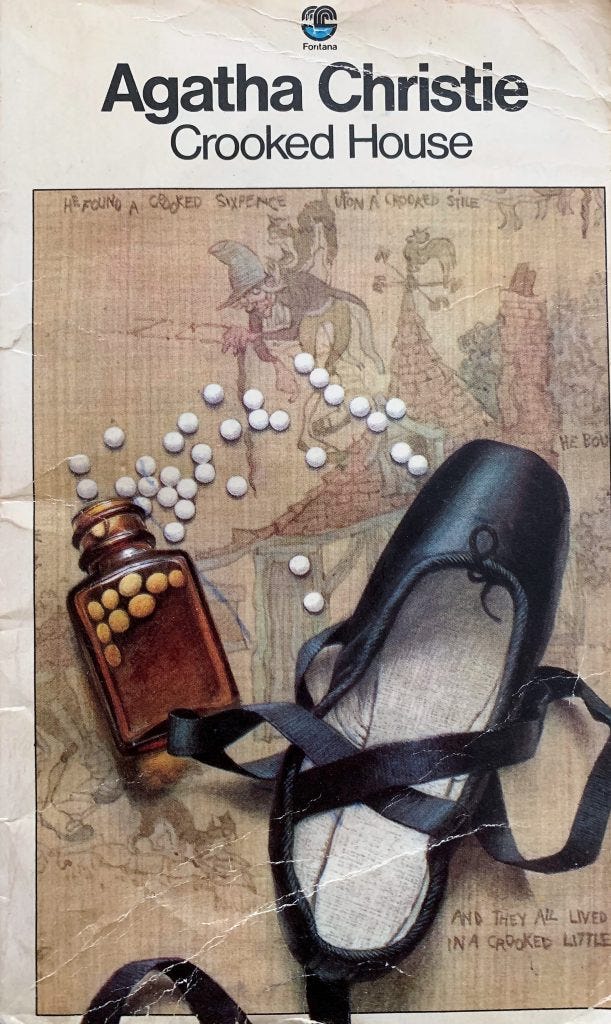

The case similarly haunted Agatha Christie; it runs like a motif through her 1949 novel Crooked House, in which one of the characters, Magda, is a theatre actress with ambitions to play Edith on the stage:

‘I know just how I’d play it—commonplace, silly, make-believe up to the last minute and then… And then,’ whispered Magda Leonides, her eyes suddenly widening, her face stiffening, ‘just terror….’

Beneath these surface references lies the deeper motif: the discovery of a condemnatory cache of love letters, written by the murder victim’s wife to her younger lover. This is a direct allusion to the Thompson-Bywaters case. It was Edith’s letters to her lover Freddy Bywaters, a merchant seaman aged twenty (more than eight years her junior), which constituted pretty much the entirety of the evidence against her when she stood trial - along with Freddy, the admitted assailant - for the murder of her husband, Percy.

Like Edith, Percy was a City worker from East London, and the couple had risen to acquire - on their joint salary; Edith’s was slightly the larger - a house in the then aspirational suburb of Ilford.

The yellow house is 41 Kensington Gardens today. So alarmingly piquant, a century ago, was the image of violent crime in this respectable milieu that the case was known from the first as the ‘Ilford Murder’. Indeed it was thus described in a letter by T.S. Eliot, who felt compelled to write to the Daily Mail on the subject.

On the Ilford murder your attitude has been in striking contrast with the flaccid sentimentality of other papers I have seen, which have been so impudent as to affirm that they represented the great majority of the English people…

This letter was published on 8 January 1923, the day before Edith and Freddy’s execution.

Eliot was right, in that the public was so obsessed with the Thompson-Bywaters case - and with its two protagonists, whose glamour vastly outweighed that of poor dead Percy - that parts of the press did indulge in ‘flaccid sentimentality’: as here, for instance, in a 2d pamphlet written by the editor of the Sunday Express, who attended the Old Bailey trial in December 1922, which was so hot a ticket that people queued through the night for seats in the public gallery.

Let me analyse the unhealthy lure that drew a morbid mob to the guarded doors.

Three ordinary clerks! Nothing here to madden London with feverish emotion.

Why, then, all the pother? The answer is – Mrs Thompson’s letters. In them she revealed a neurotic pseudo-romantic personality, nourished on melodramatic novels and melodramatic plays like Bella Donna and Romance. She also displayed a mania for self-analysis in copious epistles to her lover that reeked of the theatre and of the novel. She stood forth as the creature and creation of a hectic and hysterical age…

Mrs Thompson made all the melodramas I have ever seen look pale and colourless. She was pale and frail and pitiful. She drooped and collapsed like a lily. She vibrated like a violin, with every plaintive note in her beseeching voice. By turns she was weak and strong, vivid and colourless, alert and inert. Never was there a more elusive enigma of a woman, subtle and artless almost in the same breath, now like a broken reed and now like steel…

If one forgives and forgets the school of Cartland style, this was a not-inaccurate reading of the situation, of the way in which the case had come to symbolize fears of post-war moral decadence, and of the spell that Edith had cast upon the country: a spell whose prurient erotic darkness included a desire for her death.

The Thompson-Bywaters case was both extremely simple, and nothing of the kind. Its complexities still perplex me. For a start it is described as a murder - self-evidently, as it was a capital crime - yet I am far from sure even about that: might it have been a case of manslaughter? On the night of 3rd October 1922, Freddy Bywaters waylaid Percy (above, right) as the Thompsons were walking back to their Ilford home, after an evening at the theatre. A scuffle ensued, creating a 44-foot trail of blood, in the course of which Percy received several slashes from a knife and a fatal wound to the neck. Freddy’s intention was clearly to have a showdown with his love rival, else he would not have been carrying a knife (in court he said that he always carried one, which I struggle to believe). But can one say that his clear intent was to murder?

Well: yes, in the context of the trial, because the ‘prevailing opinion’ - that most dangerous of things, that most satisfying of narratives, spreading like a delicious warming fire within the authorities and the public - was that the true guilty party was Edith, the seductive older woman, who had written letters to Freddy that were deemed unconscionable in their pagan Lawrentian frankness (‘He has the right by law to all that you have the right to by nature and love’). More to the legal point, the letters were deemed evidence of complicity, incitement and solicitation in the killing of her husband.

Throughout 1922 Edith wrote often about her desire to poison Percy, and asked Freddy to send her some means to do this from overseas. Yet Percy’s body, subjected to an autopsy by Bernard Spilsbury, showed no trace of any such substance having been administered. ‘The case against Mrs Thompson has failed’, stated a detective on the case; but the authorities were not having that, and continued to gather up phrases within Edith’s letters and weave them into a waiting noose. ‘What is your meaning here?’ the prosecutor asked her, repeatedly, at the Old Bailey. To which she could scarcely answer, because her letters existed in a literary sphere, and her questioner in one that was literal.

But Edith had become that most English of entities, a scapegoat. So her letters would be interpreted in whatever way the authorities wished.

T.S. Eliot, of all people, really should have understood this.

I thought it would be interesting to reproduce some of her words, from time to time, if possible on the anniversary of the day that they were written (although in fact she often wrote letters over several days, taking moments in her work schedule, her lunch hour… because even while she was passionately engaged in writing to Freddy, which was fundamentally a solipsistic exercise - a means to self-expression - she was holding down a very good managerial job in a wholesale millinery firm. Ahead of her time? I’ll say she was, with her career and her childlessness and her blatant desire to own her life; and therein lay much of the trouble. No woman then could vault those twin towers of gender and class. And when the story went wrong, there was no hiding place: Edith commanded neither protection nor pity).

What follows is a letter dated 23 June 1922, a year on from Freddy’s declaration of love to Edith; together with my own commentary on her words, an edited version of what appears in Au Revoir Now Darlint.

I have made only the smallest possible changes - purely for reasons of comprehensibility - to Edith’s idiosyncratic style, which I like to think of as Modernist, unschooled stream-of-consciousness… this was 1922 after all….

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Laura Thompson’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.