‘Perhaps Tom and Bobo, who knows?’

These were among the last words spoken by Sydney Redesdale, mother of the Mitfords, before she died on the family’s remote Scottish island, Inch Kenneth, in 1963. She was referring to her two dead children, wondering whether she might see them again. Both had been casualties of the Second World War, one at the very start and one so close to the end that it had seemed he would survive. ‘Bobo’ was Unity, the mad misfit who had attached herself to Hitler and the Nazi cause, and who shot herself on the day that Britain declared war on Germany; she survived, but the bullet could not be removed from her brain and it killed her in 1948.

‘Tom’ was the only Mitford son. I was reminded of him when I received an email last week on behalf of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, which included a link to the image below: Taukkyan War Cemetery in Myanmar, home to the grave of the Hon. Thomas David Freeman-Mitford of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps (there is also a memorial in the church at Swinbrook, where most of his family are buried). Tom died aged thirty-six on 30th March 1945, a casualty of the war against Japan, which ended eighty years ago today with more than 580,000 Commonwealth War dead.

‘A day never passes when I do not think of him and mourn my loss’, wrote his sister Diana, in her 1977 memoir A Life of Contrasts. When the news came of Tom’s death she was living under house arrest, having been interned in Holloway for much of the war along with her husband, the fascist leader Sr Oswald Mosley. ‘M. telephoned the Home Office to get permission for me to go to London… I should have gone whether it was given or not.’

Tom was a strong and enigmatic figure; as I gave up on the TV show Outrageous I have no idea whether it conveys his importance within the family, which went beyond his role as heir and sole possessor among the offspring of a y chromosome. He had an elusive quality, an ability to be whatever any of them wanted him to be, while at the same time remaining very much himself: for instance Diana believed that Tom was a convert to the fascist cause and Jessica, who had married the communist Esmond Romilly, that he sympathized with her allegiances, while Nancy fondly placed him somewhere in the middle, dancing between the extremist views of his wayward sisters and committing himself to none of them.

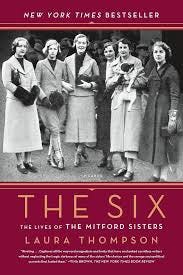

What follows, partly behind the paywall (free trial option available should you wish it), are two edited extracts from my group biography The Six, sketching Tom’s brief life and death.

Tom was born in 1909. Very close in age to Diana (seated above on her mother; Nancy is on the left and Pamela at the front), she regarded him almost as a twin. He was a perfect distillation of the Mitford looks and cleverness. The qualities of the family collected themselves together in him, breeding a man who did not, in worldly terms, achieve all that he might have done, but who left a mark simply by what he was. He was a refined product, with an impassive countenance and a fastidious mind: ‘with him,’ wrote his lifelong friend and schoolboy lover, James Lees-Milne, ‘the second best simply did not pass muster’. His rarefied tastes – Milton, Schopenhauer, Bach, Wagner – communicated themselves to his sisters, Diana in particular, who took with them his deep and complex love of Germany. At Batsford Park in Gloucestershire, the first and grandest Mitford family home, when Tom was prepared for his prep school, Nancy had been spurred to academic rivalry with him. Later, Jessica’s sense of stultification was alleviated by the literature that Tom inspired her to read.

After Eton – which he left in 1927 – he travelled to Europe, and stayed for a time in Austria at the ancient Schloss Bernstein belonging to the Hungarian count, Janos von Almasy. It has been suggested that Tom had an affair with Almasy (this would also be said of Unity). There is no evidence for this, other than his youthful predilections; according to Lees-Milne the adult Tom slept only with women. Subsequently he spent time in Berlin. Something in that thunderous, uncompromising culture spoke to him.

A gifted pianist, Tom had dreamed of a musician’s career, but in 1929 began studying for the law at Inner Temple. He needed to earn; although his father gave him an allowance there was no real financial safety net. He entered the chambers of Norman Birkett, an esteemed KC, and in 1935 was part of the defence team for Alma Rattenbury, who was accused of conspiring with her much younger lover to murder her husband. This was one of the most sensational criminal trials of the decade; in her debutante year Jessica sneaked in to watch proceedings at the Old Bailey, to which her father reacted in the manner of his alter ego Uncle Matthew when his children mentioned Oscar Wilde.

Tom was a sleek social animal. His close friends included his second cousin Randolph Churchill – despite an age difference of thirty-five years, he was also friendly with Winston – and he had lots of girlfriends. It was thought that he might marry pretty young Penelope Dudley Ward, but (in the style of the then Prince of Wales) he preferred women of the world like the Countess Erdody, the married Princesse de Faucigny-Lucinge, or the Austrian dancer Tilly Losch. Perhaps their extreme sophistication was the best antidote to all those clamorous sisters – playing hard to get was never a Mitford thing.

But Tom liked women, which he might easily not have done having grown up surrounded by so many, so strong in personality, so energetic even in their boredom, so relentlessly competitive – including for his attention. He could have gone down the Branwell Brontë route and decided to be overwhelmed. He could have been embarrassed by the girls, taking the side of his male friends against them. Instead he was extraordinarily good to Nancy when she was trapped in her futile passion for Hamish St Clair-Erskine, with whom he himself had had an affair at Eton (something that Nancy decided to ignore); in 1929 he rescued her from the Café de Paris, where she had gone with Hamish with 7½d between them. ‘We were panicking rather,’ she wrote to a friend, ‘when the sallow & disapproving countenance of old Mit was observed . . .’ Tom lent Nancy £1 and swept her away to another nightclub: perfect brotherly behaviour. He could have become petulant, demanding, anything he chose really, given that he was – like Alexei, the heir to Tsar Nicholas II – the sole prized boy. Instead he went the other way, and dealt with it all as if it was the easiest thing in the world. He was the embodiment of an overused concept: cool. True cool does not exclude warmth, but Tom always had the ability to keep himself at a slight distance, to make others want to please him. The sisters to whom he was closest – Nancy and Diana – both ended up with men who were always at a remove, who made the women come to them.

Despite the mutual affection, which really does seem to have been cloudless, he was very different from the girls; for instance he suffered from depression, whereas they had that iron will to happiness. He enjoyed their rippling flurry of constant jokes, but did not have that same instinct to make absolutely everything funny. And he remained a mystery. Later his sisters would tear themselves to pieces over the nature of his political allegiances. Unlike the Radletts in The Pursuit of Love, who ‘tell’ everything, Tom was the male equivalent of exquisite Polly Hampton in Love in a Cold Climate, who burns with emotions but keeps them entirely to herself. Polly is to some degree based upon Diana; yet even she, enigmatic though she was, did at least ‘explain’ herself in letters and writings – very few of Tom’s letters survive. They are friendly and perceptive but have nothing of the Mitford idiom. In 1930, for example, Tom describes to his mother a flight along the English coast in a ‘7 man unit’ whose passengers included Churchill and T. E. Lawrence: ‘It was very amusing flying very low over the edge of the sea and jumping the piers at Brighton and Littlehampton, to the astonishment of the people there . . .’

That same year Tom holidayed with his parents and assorted sisters at St Moritz, where they skated constantly. This was a family obsession. As a girl Sydney Redesdale had loved skating, and had a passion for her instructor: ‘I would even let him kiss me,’ she wrote in her diary. Her husband David, still with that excess of energy in his early fifties, often visited the skating rink in Oxford with his brother Jack, where both men flirted gallantly with the Austrian instructresses. Unity won a medal for skating (although on one occasion she fell on her face, having failed to put out her hands in time: ‘I was waiting to see if nature would prompt me’). Tom was talented enough to partner the Olympic champion Sonja Henie (who skated through several Hollywood films), while Deborah was actually invited to join the British junior team, although her mother turned this down without telling her of the offer.

Also on the St Moritz trip, a companion of the urbane Jack Mitford, was a glamorous chorus girl named Sheilah Graham, who later became a hugely successful Hollywood columnist and the last love of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Almost uniquely, she was fascinated by the Mitford men rather than the women. Tom, whom she described as ‘one of the handsomest men I had ever seen’, was naturally the focus of her fantasies. ‘Perhaps I could found an aristocracy of my own. And I would choose Tom Mitford to be the father, and my sons would look like Saxon kings.’

Now a second extract, about the circumstances of Tom’s death.

… Tom, who had fought in Libya and Italy with the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, came back to England in 1944 as a major. In July he was in London on leave. By chance, he and Nancy met James Lees-Milne outside the Ritz. ‘He almost embraced me in the street’, wrote Lees-Milne in his diary, ‘saying “My dear old friend, my very oldest and dearest friend”, which was rather affecting. He looks younger than his age, is rather thin, and still extremely handsome.’

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Laura Thompson’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.