I was going to post something else, then I saw the date and decided that I must instead release this, somewhat expanded, from behind the paywall…

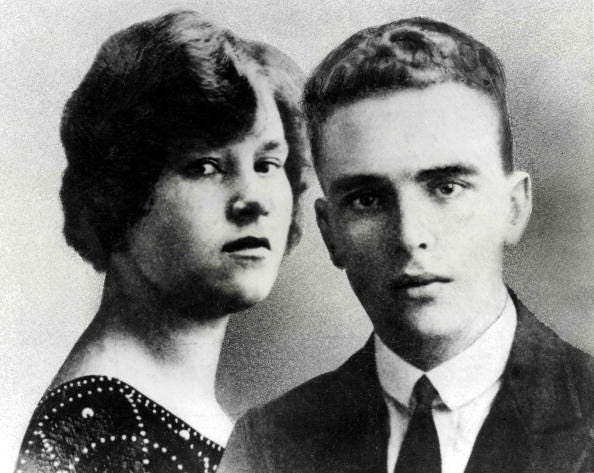

Today, 102 years ago at 9am, Edith Thompson and Frederick Bywaters were hanged simultaneously for the murder of Edith’s husband, Percy. Edith, who had turned twenty-nine on Christmas Day, died at the now-demo…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Laura Thompson’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.