There is a lady in this town, who from the window of her house has seen such as you going past at night, and has felt her heart bleed at the sight. She is what is called a great lady, but she has looked after you with compassion as being of her own sex and nature, and the thought of such fallen women has troubled her in her bed.

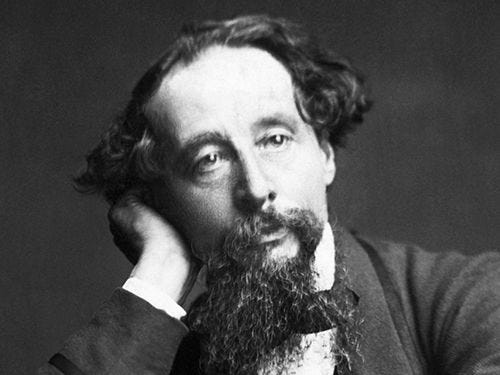

The words of Charles Dick…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Laura Thompson’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.