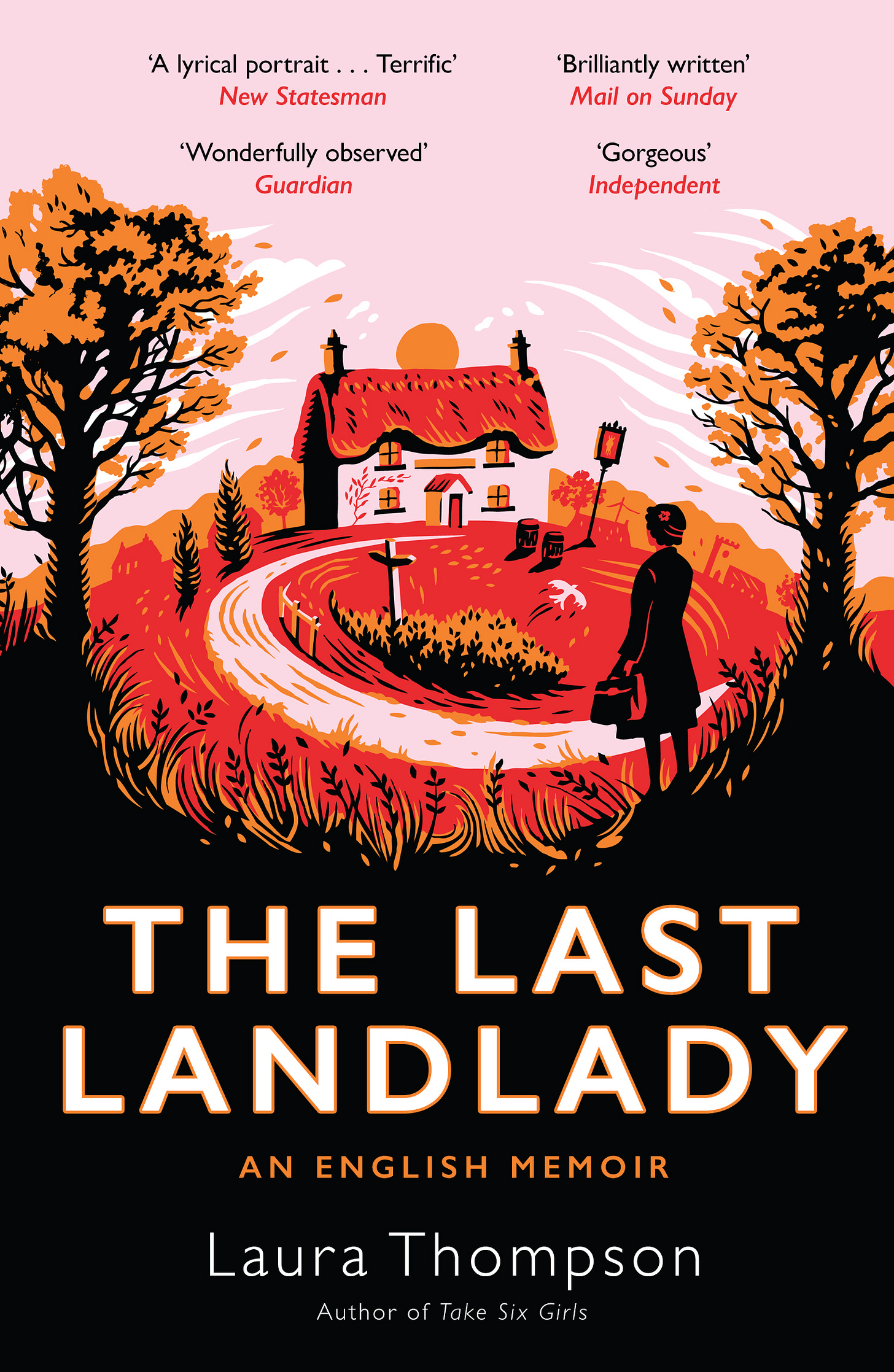

Memoir being all the rage at the moment, and maybe even for a few more days before the Salt Path narrative changes course and people start saying who needs truth anyway, I thought I would seize the opportunity and post the opening of my own memoir: The Last Landlady.

Which is all true.

‘I am for the truth, me’, says Poirot, which in a memoir does not mean that things are not elided, names changed, incidents exaggerated/shaped/ignored… the joy of that particular genre is that the fact of it being a ‘genre’ can almost be forgotten, it is simply a story. And stories are manipulable. But the essence of a memoir must surely be truthful, else one is breaking a pact with the reader.

I always remember the magnificent Alan Carr (with whom I once spent a delirious day filming about Agatha Christie: he is a super-fan) cutting through nonsense on A Good Read, after his fellow guest had picked a superior misery memoir for their book choice. He reacted to it with a penetrating scepticism, disarmingly expressed, with words to the effect of: you wonder if this is all true, but you can’t really say so because it’s all so sad, and then what if you’re wrong?

Of course he was right to say this. A lot of memoirs are bound to be suspect. I once knew a man who wrote a pack of highly persuasive lies about being adopted (the book was pulled, when those who knew the truth intervened, but a few years later it might not have been). Being an author is a bit of a desperate business, sometimes, and it is tempting to say absolutely anything that will sell. In a world where some people revere Meghan Markle for telling her truth, rather than the truth, as if this were an act of feminist autonomy rather than a sophistry whereby one can come out with as many lies as possible, who cares about a few dodgy memoirs? Surely what matters, about the unreliable Salt Path narrative, is that it had a life outside the book, affecting ‘real’ things like charities, serious illness and other people’s money? Surely that is the essence of this particular story, rather than the shifting moral question of whether/ how far it is acceptable to lie in print?

Although the two are intertwined… Muriel Spark really cared about literary integrity, which is good enough for me. Her 1988 novel A Far Cry from Kensington is a short spry hymn to its importance. Indeed anybody who loves books should care, or at least I believe so. In a Note a couple of days ago I wrote that a reader’s instinct, what Muriel called a sixth ‘literary’ sense, can often tell about these things, just as it can tell human writing from AI, and that what really matters is keeping these instincts in the best possible order. I do absolutely believe the people who said that they felt something was a bit off when reading the Salt Path, but that they were probably wrong to feel that way, that It Must Be Me rather than everybody else; such is the power of literary hype, or indeed any kind of hype.

So this extract, which is for paying subscribers and has a free trial option, is about two endangered species: the memoir (possibly) and the pub (definitely). Truly I do not know how much longer pubs have in this country. Sometimes a Substack charmer will pop up and tell me that pubs deserve to be extinct, they are not female spaces (excuse me, they are) and alcohol is a poison (as if nothing else is) and I am defending the indefensible. Well: that is an opinion, and as such fair enough, although I do invite those who hold it to read the book, because it is about pubs in a far wider sense than merely places in which to get drunk - they were stitches in the social fabric, celebrations of ordinary human pleasure, warm beacons of sanity, and I feel that they are dying at a time when we need them more than ever.

The Last Landlady is in fact about one of the most precious things that we possess, which is memory, the essence of memoir: I can still feel the almost physical pleasure of uncovering and identifying memories from my own childhood, some of which was spent in my grandmother’s pub. She really was called Violet (other names were changed in the book), and she was the first woman in Britain to obtain a publican’s licence in her own name, not as a wife or widow. That, I believe to be true.

The book was published by Unbound, in happier days for that company, so I hope to have the rights back soon.

When I think of my grandmother, it is thus: seated on a high stool, her stool, in the negligent but alert position of a nightclub singer. Behind her, a cool brick wall, whose edges made little snags in the satin shirts that she wore loose over trousers. One of her hands rested on her thigh, not quite relaxed, holding a glass.

Her hair was white but not a grandmotherly white. She went regularly to the salon on the top floor at Harrods, a fairyland pink parlour in those days, its air dense and shimmering with little starbursts of Elnett. She would come home with tales of her hairdresser’s love life (somewhat pitiable) and green and gold bags full of Estée Lauder cosmetics. From middle age onwards she disdained most products that were not by Estée Lauder, and there was never any arguing with her. The collars of her shirts were impregnated with Alliage scent, and the Re-Nutriv cold cream on her dressing table bore the marks of her fingers dragged across its surface, like little furrows in snow. She wore dark foundation and a deep red lipstick. Even now I feel that I am letting her down if I do not paint my lips.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Laura Thompson’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.