Let's get festive

Dull care is dull

I was going to post something rather serious today, but I suddenly thought: sod it, it’s December. This year has been shall we say mixed (the book-from-hell, for which I still patiently await payment - how nice it would be to have a reliably working computer and a replaced tooth filling!) and I am in the mood to celebrate its ending.

Also, I find that I keep thinking about Tom Stoppard, who for all his intellect always had a grasp upon the importance of pleasure in what he wrote. More of that, is what I want from 2026. More jokes, more humour, more civilized delight. This has been a dour decade so far, in fact I sometimes feel that I’m living in 1651 with wifi. and I suspect that I am not alone in being heartily bored with it.

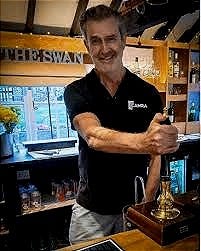

So here is Rupert Everett, not a man of the Cromwellian tendency, pulling a pint.

A magnificent actor (notwithstanding the occasional sabre-flash of Stoppard, he was so much the best thing about Shakespeare in Love) and a deeply humorous one (if you have not yet heard him singing Love is in the Air in the voice of the headmistress of St Trinian’s, duetting with paramour Colin Firth, then I recommend it), Rupert is also one of thirty people who did volunteer bar shifts at his local, The Swan at Enford in Wiltshire, to keep it going when the tenants moved out. Like almost every pub in this country, this lovely old place was under threat of permanent closure. Now, one hopes, it has been saved.

‘Times are hard for rural pubs’, he said earlier this year, ‘and this is the heart and hub of the village. I think that it is important to express my support.’

I really love this, and what it says about both the man and the pub. It says that here is an actor who doesn’t spend his life doing auditions on his phone but is engaged, out there. An actor with a sense of place. A sense of fun. Once upon a time, rather a lot of actors had that. In fact one can quite easily imagine a good many of the old-style persuasion positioned happily behind a bar, even a great star like Laurence Olivier, with his London taxi cab and his slight vaudevillian quality. Today, not so much. James Norton offering ice and a slice, I somehow can’t picture it.

But publicans, too, have changed so profoundly: the good ones were like what actors used to be. The personality required for the role was akin to that of a performer. This, for instance, is a description of my grandmother, the first woman to obtain a publican’s licence in her own right (ie not as a wife), for whom my book The Last Landlady is named:

In style and demeanour she most resembled an old-style theatrical performer, a semi-retired Coral Browne or Hermione Gingold. ‘She should have been on the stage,’ my father used to say. In fact that wasn’t quite right. She had her stage already.

For a pub is a theatre in which people are playing themselves. It is a public house, after all. This is a deceptively simple title, a perfect definition of the paradox that one is at home, but also escaping from home. One is relaxed, but bracingly relaxed. The proper pub is a place where people become their public selves, rather than their private; the division of personality that makes life a business worth engaging with, and that has all but disappeared into the deadly vortex of the smartphone.

My grandmother, who had a lot of self to play, played herself better than most. She learned to do so at such a young age that it became innate; but she also saw it as a duty, and in her staunch, frivolous way she believed in duty. Put on a show, be fun, drown your sorrows, don’t be a bloody bore.

The Last Landlady, my elegiac homage to the pub and to my grandmother, is going to be reissued next year, which for me is a wonderful thing but also, more broadly, a timely one. Throughout 2025, pubs closed in Britain at a rate of more than one per day, and the Budget will merely accelerate that statistic. For some pubs, business rates will increase by 400%. Sometimes I read that the slow death of the traditional pub is a good thing, because alcohol kills and pubs are sexist (bad pubs are every kind of ‘ist’, but that should not condemn a whole industry). I have similarly read that widespread closures of High Street betting shops are to be applauded, because gambling is evil (addiction is an evil, but that is not quite the same thing).

Yet it seems to me that our obsession with pushing out vice - although not crime - can, in its unbending puritanism, lead to consequences that are unforeseen and unkind; sometimes humans need a little vice in their lives. Think of Stoppard and his elegant trail of cigarette smoke. Where I grew up in the rural Home Counties, pubs were not just about getting plastered, although of course that happened; they were about communality, a kind of unselfconscious democratized humanity, which didn’t mean that everybody was nice or even welcome, just that they were accepted. Similarly, in their more charmless way, the local betting shops. I think of the widower still living near my mother, who I used to see on dog walks and whose otherwise solitary life revolved around his daily visit to the nearest bookmaker, where he could study form in semi-taciturn companionability. So much better, surely, than the twin websites of the Racing Post and ladbrokes.com?

I don’t mean to romanticize, simply to be realistic.

I have a feeling that the survival of the pub is very, very important in this presently somewhat benighted country. Governments (not just the present one) seem not to care. Ineffable concepts such as are represented by the pub cannot be computed by the Treasury: therefore, forget it. But sufficient numbers of the public, I hope, feel differently.

The new publishers of The Last Landlady have asked for a new introduction, which with luck will not be a funeral oration. When the book was reissued by Unbound in 2021, I wrote an afterword in which I considered the future of the pub in the aftermath of lockdowns and the like. It is reprinted here behind the paywall: the uneasy mixture of hope and concern is still, pretty much, what I feel.