Do you know the film White Mischief, released in 1987? I watched it very recently, for the first time in about fifteen years.

It is based on a book by James Fox about the so-called ‘Happy Valley set’, a gang of privileged British who settled in colonial Kenya during the interwar years. Their name derived from the region in the Wanjohi Valley where they congregated, nicknamed ‘Happy’ by the first colonial farmer in the area, who found the land congenial to his crops. But it was also peculiarly suited to this set, whose hobby was pleasure, of many and varying kinds, until the 1941 fatal shooting of their leading man - Josslyn Hay, 22nd Earl of Erroll - snapped the gilded circle within which they lived. Eleven years later came the Mau-Mau rebellion, and in 1963 Kenya gained its independence. End of story.

But what a story! An enclosed world unto itself, plus an unsolved murder… Narrative Nirvana. I fairly devoured the White Mischief book, although I did not love it, and was intrigued to see the film again, in the hope that I would like it better second time around. I didn’t. I still thought it disappointing. For all its cultivated air of unblinking sophistication there is a hint of the excitable sixth-former in its imagining of the Happy Valley Set, something BBC-does-decadence: laconic drawling, performative nicotine-inhalation and carmine lipstick that neither smoking nor sex can smudge. Not unlike that recent Towards Zero, in fact.

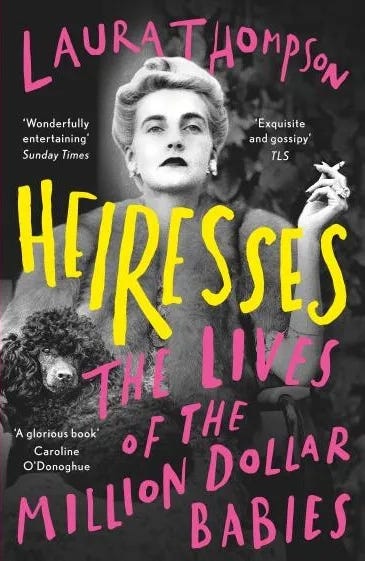

It has moments, for sure. Joss Ackland as Sir Jock Delves Broughton, chief suspect in the Erroll murder, is utterly superb. So too is Geraldine Chaplin as the bought, taut wife of a reptilian Trevor Howard: ‘Do you sleep with your husband’, she says, in a choked mutter, to the radiant Greta Scacchi (as Diana Broughton, married to the three-decades-older Jock) and a whole world of transactional living is bleakly conjured. Murray Head appears, always a good thing, and peak-period Charles Dance is pretty unimprovable as Erroll. But the relationship between him and Diana - which is the heart of the story, and probably the motive for the murder - does not convince me, on any level other than the aesthetic; at one point he says to her ‘I want you to save me from myself’, which it is literally impossible to imagine the real Erroll (Scottish aristo, professional seducer and supporter of Mosley’s British Union of Fascists) ever saying. And Greta Scacchi is far too much of an innocent, almost a victim of her own gorgeousness, rolling enormous Bambi eyes at the grown-ups like that other Diana, whereas in truth Diana Broughton was a battle-hardened gold-digger on the make: ‘tough-looking, nakedly vampish, with a touch of the gangster’s moll despite her rigorous chic’, as I wrote in my book Heiresses: The Lives of the Million Dollar Babies.

I also wrote about colonial Kenya at that time:

… full of European settlers, what Evelyn Waugh described as “English squires on the Equator”; on the one hand was the alien glory of a giraffe, on the other a club serving Brown Windsor soup and vast amounts of alcohol. “Everyone drank about ten pink gins before lunch,” Waugh recorded in his diary during a visit to Kenya in 1931. There was also a colony within a colony, the Happy Valley set, about whose delinquency so much has been written. These people were decadent in a bone-deep way. They were the same kind of socialites as would be found in London; yet somehow they were not quite the same, because the world in which they operated was different. It was their creation, it was all that there was, and within those giant open spaces it had a strange, unhealthy exclusivity.

Happy Valley - and the murder of Joss Erroll - feature in my book because one of the heiresses I chose to write about is Alice Silverthorne, later de Janzé, born in 1899 to a timber millionaire and a Chicago socialite. She appears in White Mischief, played by Sarah Miles (marvellous, in that borderline bonkers way of hers, but not quite right) and portrayed as a junkie, which she was not. It is in this film that Alice speaks the famous line - ‘Not another fucking beautiful day’ - which I came to see as the heiress’s cri de coeur.

One of Erroll’s many lovers, Alice was also a suspect in his murder. Although the crime was almost certainly committed by Jock Broughton (acquitted by a white settler jury) some questions remain, not least whether the ageing drunken Jock had the straightforward physical capability. And Alice, as will be seen, had form when it came to shooting her exes.

I became briefly rather obsessed with her, as can happen when one writes about a person: she was such a romantic figure, so richly frustrating, a wild girl with the demure look of an off-duty member of the Ballets Russes, whose lion cub Samson was her true soulmate. One of those heiresses whose money (as Noel Coward wrote of Barbara Hutton) was always between her and happiness, she scattered havoc - mainly for herself - and ‘harboured an equally fervent life force and death wish.’

Her mother died when she was seven, her father lost custody and she was raised by her uber-correct Armour relations (Chicago royalty). After her wartime debutante ball (‘like taking Samson the lion cub to Henley Regatta’) she started going to nightclubs with a Prohibition-dodging mobster. In 1921 she went to Paris and reverted to type by marrying Comte Frédéric de Janzé - courteous, Cambridge-educated, excellent on paper - although this, too, was transactional, and traced a familiar pattern for the times. The American heiress acquired a title, the European aristocrat got money. While his family was besotted with the Silverthorne inheritance, however, Frédéric was under the spell of Alice herself.

Almost certainly the feeling was not reciprocated. Alice fell almost immediately pregnant with the first of two daughters, and grappled with her new relations, with whom she shared the ancestral chateau in Normandy.

She was part of a world into which she did not actually belong, and by which she was bored to the point of rage. Therein lies a paradox: the heiress always has the means to buy escape, but for that very reason she never quite escapes.

Yet the illusion that she might do so came in 1925, when she travelled to Kenya for the first time with Frédéric. She was disorientated and transfixed by the place - the deep shadows cut by the blinding sun, the absolute darkness of the night sky, the proximity of the majestic animals - and above all, perhaps, by the belief that here was freedom.

Into this cruel, beautiful, and beguiling world came Alice, and very soon she began an affair with Joss Erroll that would continue, on and off, until his murder in 1941.

What follows behind the paywall (free trial option available) is a further, edited extract from Heiresses: a continuation of Alice’s unhappy life story, and how the death of Lord Erroll precipitated her own.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Laura Thompson’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.