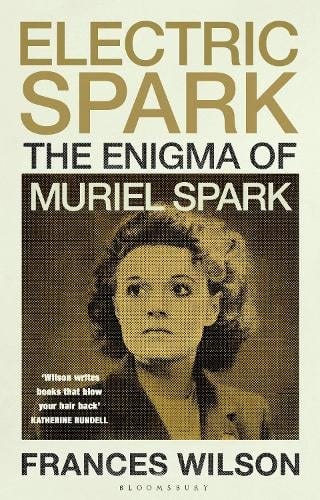

I was sent a proof copy of Frances Wilson’s Electric Spark, a biography of the goddess Muriel published by Bloomsbury in June, which I am reading and relishing. The wonderful

has promised a review of it: a treat to anticipate. Meanwhile I am feeling so energized, so braced, so sparky indeed, wandering around the inside of that singular literary mind, that I wanted to revisit an old post, expand it considerably and send another tribute.I find it impossible to feel depressed, or stressed (although I am, objectively, the second of these at the moment), when I am inside Muriel’s head. She comes at life in such a way as to make all that irrelevant. Different things shine, different things matter. I remember - a tiny instance - reading a piece that she wrote, about winning a short story competition and giving an impoverished friend some money: ‘he never forgave me’ was her punch line, or words to that effect. Which renders a situation instantly light and hilarious. In a very Muriel phrase, it makes merry with it. As does this, from the 1988 novel A Far Cry from Kensington, at the end of a phone call in which the magnificent heroine Mrs Hawkins deals with an unwanted admirer: ‘He gave me a number and I repeated it slowly enough to make out that I was writing it down, which I wasn’t.’ Even death is less of a worry when one reads about the ghost in the story ‘The Portobello Road’, sauntering through her half-world and haunting the man who murdered her.

Electric Spark is brilliant on Muriel’s relationship with ghosts. The book’s focus is upon the early part of her life - the making of the artist that she would be, publishing her first novel (The Comforters) in 1957 at the age of thirty-nine: ‘how Muriel Spark became Muriel Spark, and why it took her so long’. So cleanly-conceived is The Comforters that it is extraordinary to consider the struggles that went before: the youthful marriage to the mentally afflicted Sydney Oswald Spark (S.O.S.); the frightful lover Derek Stanford, who is reimagined (and conclusively dealt with) as the pisseur de copie Hector Bartlett in A Far Cry from Kensington; the early career as a literary biographer, at which she naturally excelled, although one can feel the clamps upon her agile talent; the year (1951) in which she earned £31 from her writing. As the novelist-narrator Fleur, a version of the young Muriel, puts it in the 1981 book, Loitering with Intent):

However sinister the theme of my Warrender Chase which was then uppermost in my mind, no one can say it isn’t a spirited novel. I think that ordinary readers would be astonished to know what troubles fell on my head because of the sinister side…

I have long adored Muriel Spark. I can’t remember when I first read her, but I do recall that I started after watching the film of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. I read the book, and was amazed by how superior it was (Maggie Smith notwithstanding), how the film had reconfigured that enigmatic, spiky shape, smoothed its edges, and drained the dangerous fun from a book so exciting to read that I can become enthralled by the shape of its minimal paragraphs (‘Sandy said: “There was a Miss Jean Brodie in her prime”’) and the placing of its semi-colons.

I have since had phases in which I only want to read Muriel. My mother and I share a particular love for The Ballad of Peckham Rye (‘Wilt thou have this woman to thy wedded wife?’; ‘No, to be quite frank, I won’t’) and the daemonic Dougal Douglas/ Douglas Dougal, who brings a kind of sexy havoc to the area of south-east London where Muriel comfortably lodged during the years of her growing fame. (Later she moved to Italy, and acquired the elegant life that in youth I fondly imagined was the norm for a writer.)

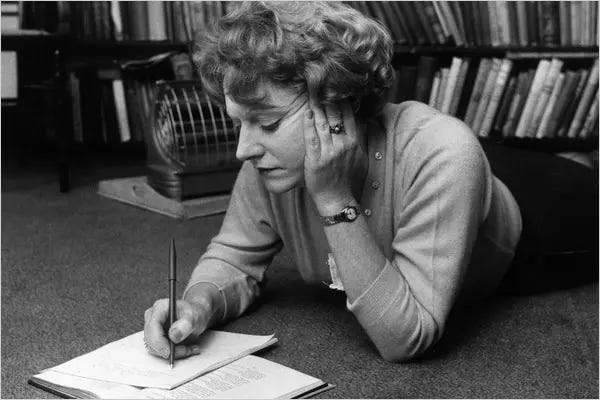

Sometimes, nobody but Muriel will do. During one of my phases I picked Loitering with Intent as my book choice for Radio 4’s A Good Read (a mistake, because it is so ridiculously hard to convey what it is ‘about’ - I remain annoyed by the fact that I didn’t do it any kind of justice). Not long before she died in 2006 I went to see her speak in London, and was almost as excited beforehand as if it were a Stones gig (although the event was something of a letdown - the interviewer did not make the most of her venerable playful radiance. There was only one memorable moment, when she described Elizabeth Taylor’s waxen, wild-wigged performance as the murderee in the 1974 film of The Driver’s Seat. ‘Well’, came the droll, vital, Edinburgh voice, ‘she didn’t look like she wanted to be murdered.’)

I have read all her books, some multiple times. I am less besotted with her uber-stark 1970s Euroland work - Territorial Rights (1979) reads to me like a pastiche of a Muriel Spark novel - and I didn’t love her Lord Lucan book, Aiding and Abetting (2000), which was surprisingly conventional in its class attitudes (posh men = bad) and its adherence to the uncorroborated gospel according to Lady Lucan (see my earlier posts on that vexed subject).

In the scheme of things, however - a scheme that also includes The Girls of Slender Means (1963), Memento Mori (1959), and some of the best short stories ever written (‘The Black Madonna’!) - these are the tiniest of quibbles. When I recently read Muriel’s New York Times obituary, which contained the assertion that, by the time of her death, her ‘reputation had already begun to sink’, I was genuinely outraged. Then I remembered another passage from Loitering with Intent:

I had known for a long time that success could not be my profession in life, nor failure a calling for that matter. They were by-products.

That unforced, robust sense of self-worth has always seemed to me the perfect response to the vagaries of literary fashion, or even opinion.

However: although Electric Spark is proving a fine counter-balance to such nonsense, I have also seen Muriel described as a ‘difficult woman’, overly non-conformist in both art and life (for instance she did the thing that several female writers felt compelled to do, and gave up primary care of her son to her own parents), and as such insufficiently valued. Do people really still think this way? What does it even mean? Who is an ‘easy woman’ - Jane Austen? THE Elizabeth Taylor (ie the novelist)? Audrey Hepburn? The Princess of Wales? It is so absurdly reductive as to become a kind of category error.

Yet I can see that there is something perturbing in Muriel’s literary vision, which disdains ‘normal’ responses - also concepts like cause and effect, or motive - and which is, like cubism, apparently skewed in its extreme clarity. The supreme example is The Driver’s Seat (1970): the tale of a woman who goes on holiday in order to be killed, in which everything is both wholly unexplained and clear as rain water. It is a work of such genius that I can only ask of it the ultimate fan’s question: ‘How has she done this?’ It is also as dark as an oubliette and downright weird, if one chooses not to see it through the Muriel prism. Which was apparent from very early on, in her biography of Mary Shelley, published in 1951 (the £31 year). In an apparent throwaway - actually nothing of the kind - she suggested that Mary would have been easier to live with had she been ‘tipsy’ a bit more often, a judgement that today might cause all manner of palpitations.

But that word tipsy - both precise and approximate; referring both to the intake of alcohol and to a kind of general human loosening - is pure Muriel Spark. Nobody else can revivify a familiar term with quite such buoyancy. Similarly: ‘I dearly love a turn of events’, says Fleur in Loitering with Intent, when she is confronted with evidence of her lover’s casual infidelity. Cold - odd - unfeeling…? I can well imagine such a reaction. Indeed it is quite usual to see Muriel described as cold and odd. Bernard Levin thought she was a witch, and Elizabeth Jane Howard writes in Slipstream that she ‘always felt vaguely frightened of her’. But to me that line of Fleur’s is pure joy; I can still remember that first sense of reading it, and of being shocked into a clear, clean, deliciously unfamiliar position.

It is a question of language, as much as anything; of what Muriel herself called the sixth sense, which she identified as a ‘literary’ sense in her autobiography Curriculum Vitae (an exercise in enigmatic honesty). And when language is used in such a way, as it were to direct the traffic of one’s sensibility, to show what is important and what is not, it seems to me the outward signifier of an illuminating sanity.

Muriel was a practising Catholic (I am intrigued to read what Electric Spark makes of her religious conversion). She was a writer who perceived the metaphysical in earthbound realities. She could also - I find this especially in Girls of Slender Means - give the impression that her words, which are few and elusive in meaning, have nevertheless been honed by a stern moral seriousness. This has a religious dimension, no question. Yet it also proceeds from her pre-conversion self, which was ‘practical, staunch, rational and broad-minded’: the words that she uses to describe Mary Shelley, and that also conjure her own Edinburgh upbringing.

Some small boys were playing football, and the ball came flying straight towards me. I kicked it with a chance grace, which, if I had studied the affair and tried hard, I could never have done. Away into the air it went, and landed in the small boy’s waiting hands. The boy grinned. And so, having entered the fullness of my years, from there by the grace of God I go on my way rejoicing.

That little passage, magical and rooted, is from Loitering with Intent. Then there are these lines, from The Ballad of Peckham Rye (1960), that sly masterpiece, in which she writes of ‘the Rye for an instant looking like a cloud of green and gold, the people seeming to ride upon it, as you might say there was another world than this.’ The infinity of imagination, rendered with a kind of shrewd economy, plus a dash of the demotic - only Muriel can create that particular blend, or paradox.

And she makes one read in a way that is truly alive, because there is no telling what might come next. The care with which she uses words goes alongside an attitude that feels gloriously airy, profoundly light; a blast of her prose every morning is a far more restorative way to start the day than a double espresso.

Nowhere is this more true than in A Far Cry from Kensington, a late novel and thus utterly secure in its direct tone, its firm principles, its solidity around which darts the mysterious spiritual element, like a firefly in a pub. It is voiced by Mrs Hawkins, a war widow of twenty-eight (the book is set mostly in 1954), who at the start of the story induces a sense of comfort in those around her, not least because she is ‘massive in size’, with a ‘Rubens quality of flesh, eyes, skin’. This is her own description: essential to her magnificence is her ability to face facts. Later she will, as she puts it, decide to be thin, but ‘in the year 1954 I was comfortable in my fatness, known as a ‘wonderful woman’ although I had never done anything wonderful at all.’

Mrs Hawkins is a great giver of advice. She works in publishing (that world brilliantly sketched; I particularly love the firm in which all the editorial staff have been employed for some terrible, pity-inducing problem that makes it impossible for authors to argue with them). She advises an old military type, who wishes to compile his memoirs, that the way in which to get the book done is to acquire a cat, who will provide a calming influence as he writes. She offers the advice that turns her, throughout the course of the book, into a slim woman - ‘You eat and drink the same as always, only half’ - and describes how to achieve the will power that is necessary for successful dieting:

You should think of will-power as something that never exists in the present tense, only in the future and the past. At one moment you have decided to do or refrain from an action and the next moment you have already done or refrained; it is the only way to deal with will-power.

Then there is this, which genuinely transformed my feelings of torment about perpetual sleeplessness.

Insomnia is not bad in itself. You can lie awake at night and think; the quality of insomnia depends entirely on what you decide to think of. Can you decide to think? - Yes, you can.

Who need self-help, when there is Mrs Hawkins?

The novel is somewhat autobiographical, and its story is not always sunlit, although it has the consolation of being recalled at a distance in time. Everything is a matter of perspective, of course, never more so than with Muriel Spark; it is a real shock to read in Electric Spark of a saga that blighted the end of her life, upon which she seems not to have had the luxury of an overview. It concerned a previous biography - by Martin Stannard - which Muriel herself had wanted written, and which caused her intense unhappiness, over what she perceived to be its erroneous interpretations. ‘She had put her life, in every sense, into the hands of a man she no longer trusted and Stannard was yoked to a woman determined to derail his book.’ This must have been utterly dreadful for her (although the Stannard biography strikes me as anodyne, if anything), and Muriel’s friends took the view that the strain of this wrangling helped to kill her. Which I can hardly bear to consider.

And yet it is as though Muriel, with her wayward insistence upon a biography in her lifetime, had deliberately created a situation like a Muriel Spark novel. There are hints of Peckham Rye, of Loitering with Intent, of A Far Cry from Kensington…

I like to think that something in her saw it that way, that somewhere inside she made merry with it.

I’m slightly embarrassed that I’ve not read any Spark except for The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, which I read years ago. There’s so much to choose from, what should I definitely not miss do you think?

Frances Wilson is such a gifted and creative biographer. I was fortunate to have her as a tutor on my MA and she made us see how many different ways there are of writing lives.